KENYA

While significant progress has been made to curb poaching and the illegal ivory trade in Kenya, the country remains a key exit point for illegal ivory destined for Asia.

Is there a need to revise the existing NIAP or develop a new one? ‘YES‘

BEST PRACTICE

The Great Elephant Census found that Kenya has a “relatively stable population” of elephants and the IUCN African Elephant Status Report (2016) concluded that significant range expansion had occurred in Kenya. Kenya has strengthened its legislative framework, with more severe penalties introduced by the new Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (WCMA). Kenya was the first country, in 2015, to launch a “Points to Prove” rapid reference guide for wildlife crime prosecutors.

The ETIS report to CoP17 noted there has been active suppression of local trade in ivory curios, which is particularly important given the large tourist industry in Kenya. The Report also stated that since 2013, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda “seem to have met with greater success in interdicting large-scale movements of ivory prior to export abroad”. The report noted that arrests had resulted from some of the seizures and extraditions from China to Kenya, and from Tanzania back to Kenya, were demonstrating effective regional and international collaboration between law enforcement agencies.

Kenya has established a well-trained Wildlife Prosecution Unit, a Regional Genetic and Forensic Laboratory to enhance prosecution of wildlife crimes through provision of admissible scientific evidence and a Joint Port Control Unit in Mombasa as part of the UNODC-WCO Container Control Programme. Canine units have been deployed at sea and airports.

However, many of these initiatives are yet to demonstrate comprehensive impact on the ground. Mombasa continues to be a significant point of exit for illegal ivory destined for Asian markets. Experts from the Nairobi National Museum, and not the new laboratory, are still being used in court as the experts to identify seized ivory based on visual examinations. A report published as recently as September 2018 found that successful prosecutions are mainly limited to low level wildlife traffickers.

KEY CONCERNS

High levels of illegal exports from Mombasa

Despite some improvements, export of poached ivory continues at a high level through the port of Mombasa.

There have been no large-scale seizures in Mombasa port since December 2016 (one shipment that month destined for Cambodia initially cleared Mombasa but was recalled on intelligence from Vietnam). Given the significant quantities of illegal ivory passing through Mombasa, the lack of large-scale seizures demonstrates either inadequate detection operations or systemic corruption (or a combination of both). Further, other than the Feisal prosecution (see below), there have been no convictions in Kenya in relation to nearly 20,083kgs of ivory seized in Mombasa (2011-16) or 26,255kgs of ivory seized outside Kenya but having passed through Mombasa (2009-16), which is equivalent to ivory sourced from approximately 6,916 elephants.

Low conviction rate and lenient sentencing

Despite there being 12 large-scale seizures of ivory in Kenya since 2010, there has only been one conviction in relation to a large-scale seizure (Feisal Mohammed Ali), and even that was overturned on appeal on 3 August 2018. The Office of the Director of Public Prosecution has appealed against the ruling and it is hoped that the conviction will be reinstated.

A 2016 report by NGO Wildlife Direct on trials after the enactment of the WCMA concluded that the proportion of convicted persons given jail sentences without the option of a fine remained very low at six per cent in 2015 and decreased to 1.1% in their 2018 report. The study found that nearly all foreigners arrested at JKIA in 2014 and 2015 were in transit and were able to leave the country after paying a fine, resulting in missed opportunities to gather information about transnational criminals and their networks. In addition, Kenya does not have a centralised national database on known and suspected wildlife criminals, which is essential to facilitate intelligence-led enforcement. In its 2018 report, Wildlife Direct found that suspects in major ivory trafficking cases were not prosecuted.

Corruption impedes effective detection, investigation, prosecution and sentencing

There is a serious concern about endemic corruption in Kenyan investigative agencies: for example, the lack of large-scale seizures in Mombasa despite large amounts of ivory moving through the port and the fact that although wildlife poaching/trafficking convictions appear to be on the rise, cases involving police/organised cartels still linger before the courts. In a case involving three Kenya-related seizures from January 2013 presently before the Mombasa courts, an NGO received serious death threats and warnings to back off the monitoring of the prosecution. In numerous cases, suspects of serious crimes have not been investigated and/or prosecuted. There were several allegations of corruption connected to the trial of ivory trafficker Feisal Mohammed Ali (including allegations of evidence tampering) and the magistrate was suspended. The strengthened laws in the WCMA will have little or no impact on serious wildlife crime in Kenya unless corruption is brought under control.

No routine financial investigations and seizure of proceeds of crime

There have been no convictions for ancillary crimes linked to ivory offences, such as anti-corruption, anti-money laundering and criminal laws, nor seizures of the proceeds of crime, although some assets were frozen in one case.

Lack of reporting to facilitate CITES decision-making

Kenya has not submitted regular and adequate NIAP progress reports to CITES and has not used key indicators in its NIAP to demonstrate impact.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NIAP REVISION / PRIORITY AREAS OF IMPLEMENTATION:

While Kenya has made significant progress, several key concerns remain, particularly corruption. Therefore this is not the appropriate time for Kenya to exit the NIAP process, although it could potentially exit the process in the future when these concerns have been effectively addressed.

- Significantly increase resources for customs officials at all exit points, especially in Mombasa, resulting in reduction of ivory being exported from Kenya

- Enhance international collaboration with key source and transit countries

- Prosecute corrupt officials facilitating ivory trafficking, particularly in customs and the judiciary

- Increase prosecutions of high-level trafficking

- Use ancillary legislation to prosecute offences linked to wildlife crime

- Strengthen regular collaboration between all relevant law enforcement agencies

- Create a national centralised database on known and suspected wildlife criminals

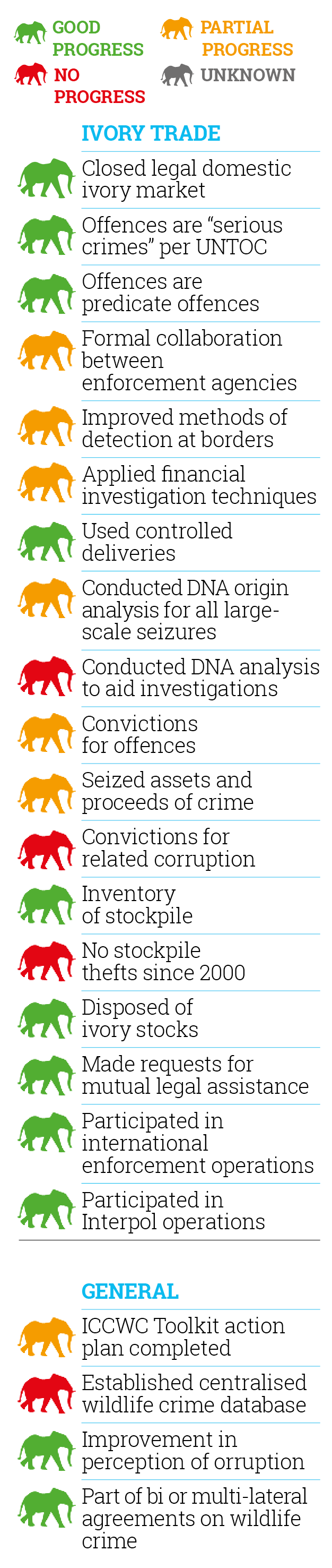

Key indicators of NIAP progress