Overview

The coronavirus pandemic of 2020 saw the world come to a virtual standstill, with global lockdowns disrupting or halting transport and trade routes and travel.

The hopes that illegal wildlife trade activities would also be disrupted or halted were largely misplaced – as millions of people worldwide adapted and started working from home, so too did the traffickers.

Over the past decade, we have seen a shift of focus as organised criminal networks involved in illegal wildlife trafficking from the continent of Africa to markets in East and South-East Asia have further turned their attention from East and Southern Africa to West and Central Africa, moving their operations to both source and export increasing quantities of illegal wildlife.

Much has been made of Nigeria’s role in the illegal wildlife trade; in 2015, the country emerged as the primary exit point for illegal wildlife, implicated in the seizures of more than 30 tonnes of ivory and 167 tonnes of pangolin scales.

But this is not Nigeria’s problem alone; the sheer scale and volume of the illegal wildlife trade makes this a regional issue, as evidenced by the severe decline of elephant and pangolin populations in neighbouring countries and local extinctions of certain elephant populations.

Introduction

West and Central Africa are now major sourcing and export hubs for the illegal trafficking of elephant ivory and pangolin scales to Asia.

The criminals involved in wildlife trafficking seek out operational environments that are well-connected to consumer markets and present minimal law enforcement risks.

Growing economic integration including road, air and maritime transportation infrastructure development facilitate the means by which wildlife can be exported to Asia. Indeed, Nigeria stands out in the region (and the continent) as one of the ‘Big Five’ economies in Africa, projected to be the fastest-growing economy in Africa by 2050. Yet this is in stark contrast to widespread corruption, poor institutional frameworks and weak governance which undermine economic growth, foster inequity and facilitate crime.

EIA has identified Nigeria as a key country in the consolidation, packing, sale and export of high volumes of ivory and pangolin scales, sourced largely from outside the country from neighbours throughout West and Central Africa.

Traders in Lagos are sourcing illicit wildlife products from suppliers in Cameroon and selling to customers in Nigeria and abroad, predominantly Vietnamese and Chinese buyers. They offer services as ‘clearing agents’ working with corrupt Government officials, particularly in the customs departments of specific sea- and airports, to export ivory and pangolin scales in staggering quantities which continue to leave the shores of Nigeria undetected, destined for Asian markets.

These operations are highly organised and sophisticated, spanning multiple jurisdictions and not only violate wildlife or environmental protection laws, but also other laws related to organised crime, including conspiracy, money laundering, customs fraud and corruption.

At risk: Status of pangolins and elephants in West and Central Africa

The most recent comprehensive population survey of elephants in West and Central Africa was conducted in 2016. Results indicate that populations in West Africa are particularly vulnerable to local extinctions due to herds being mostly small, fragmented and isolated.

Poaching is one of the primary reasons for the local extinction of certain elephant populations in West and Central Africa. Urgent improvements in law enforcement and investment in conservation is vital for the survival of the last remaining wild populations in this region.

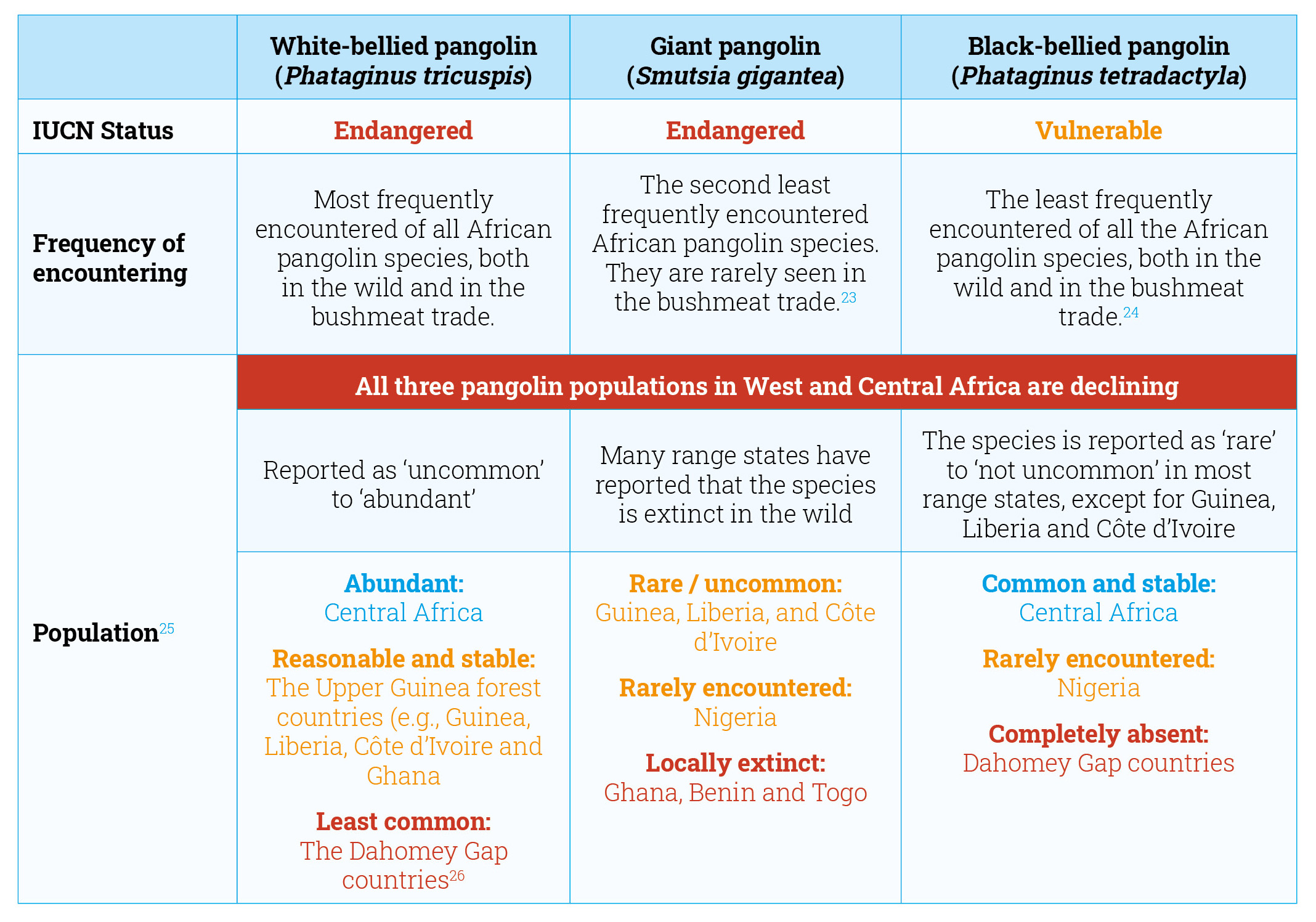

Pangolin populations of West and Central Africa

All roads lead to Nigeria

Map illustrating the sourcing routes and transit types of ivory and pangolin scales smuggled towards Nigeria based on EIA’s seizure database and investigations from 2018-20.

Following the DNA trail: Sourcing ivory from the forest elephants of West and Central Africa

DNA analysis of large-scale ivory seizures (>500kg) between 1996 and 2014, conducted by researchers at the University of Washington, has confirmed that a significant portion of ivory trafficked globally is sourced from elephants in West and Central Africa, confirming that these elephant populations are at severe risk from poaching. The analysis found that:

- the majority of African forest elephant ivory intercepted between 1996 and 2005 came from the eastern part of DR Congo;

- since 2006, up to 93 per cent of forest elephant ivory seized globally came from the Tri-National Dja- Odzala-Minkébé (TRIDOM) region and the Dzanga Sangha Reserve in Central African Republic;

- a smaller quantity of forest elephant ivory came from Burkina Faso, Benin, Ghana and the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire.

Scientists are currently developing a DNA analysis system for pangolin scales which would determine the geographic origin and identification of pangolins seized and highlight poaching hotspots.

This work complements ivory assignments because 25 per cent of all large seizures of pangolin scales are comingled with ivory.

Above left, in 2012, Royal Malaysian Customs seized 6,034kg ivory shipped from Togo; above right, 3,900kg ivory were seized in Togo in 2014. DNA analysis showed some of the tusks seized in Togo and Malaysia came from the same elephant population, suggesting that the same network may have been involved in exporting these large-scale shipments of ivory representing hundreds of dead elephants.

Key African countries implicated in ivory and pangolin scales trafficking

A shift in the epicentre of illegal ivory and pangolins trade over the past decade, measured by the quantity of seized contrabands linked to each country.

Large scale transportation of ivory and pangolin scales

Since 2015, Nigeria has been the world’s primary exit point for ivory and pangolin scales trafficked from Africa to Asia. During the past five years, the country has been implicated in more than 30 tonnes of ivory and 167 tonnes of pangolin scales seized globally, the equivalent of at least 4,400 elephants and hundreds of thousands of pangolins.

Throughout 2019 and 2020, EIA undercover investigations in West and Central Africa have provided remarkable insights as to how ivory and pangolin scales are being trafficked from across the region into Nigeria.

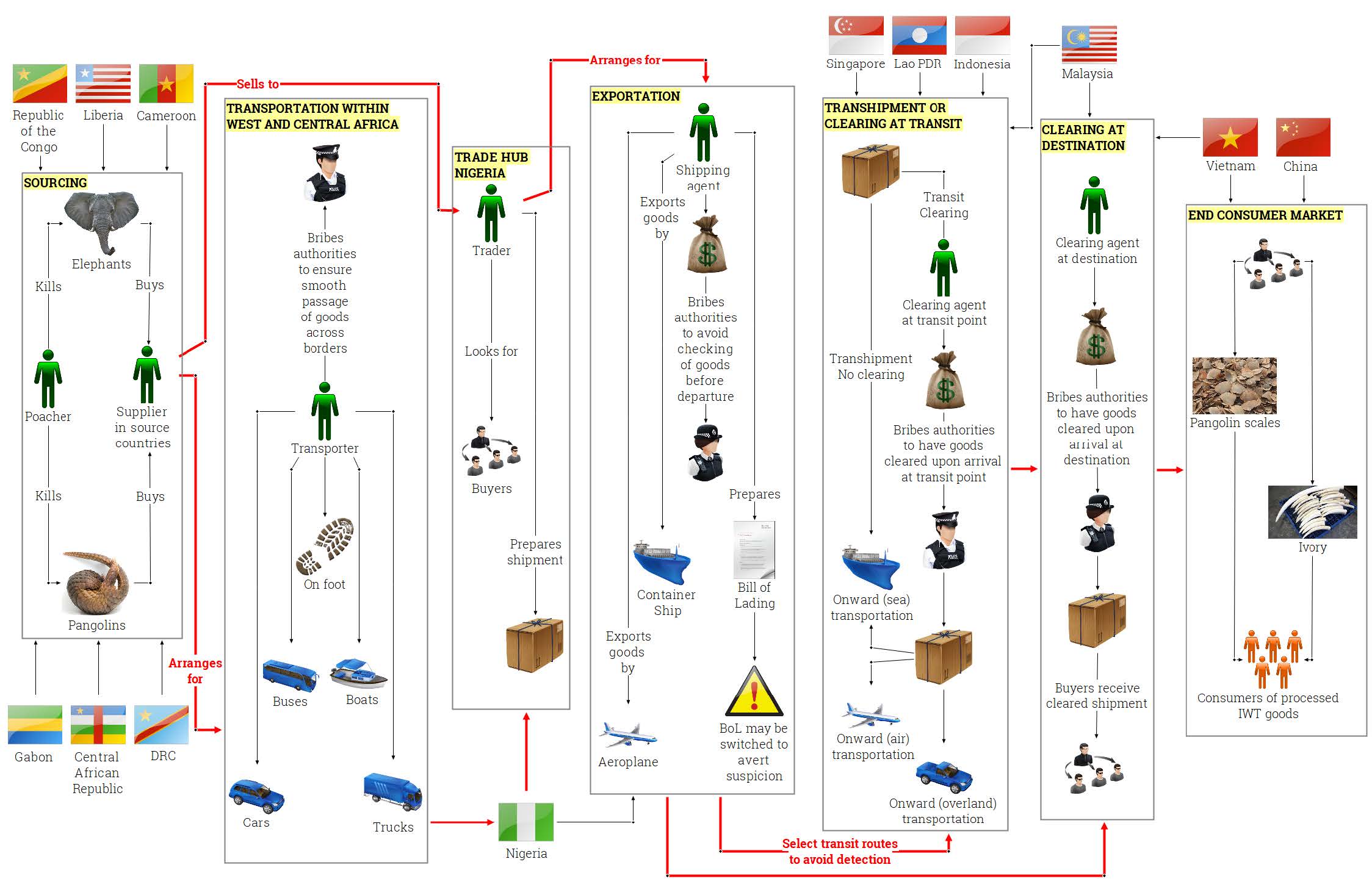

Traffickers use buses or trucks from Liberia and the Central African Republic, speedboats from Gabon and Cameroon, canoes or simply walk across the Cameroon-Nigeria border to transport illicit wildlife products.

China and Vietnam are the primary destination countries; for ivory and pangolin scales trafficked to both countries, maritime shipments are sent from West and Central Africa with one or more stops en route. At each stop, either ‘transhipment’ or ‘transit’ takes place. Transhipment takes place when the container is moved from one ship to another for onward transportation to Vietnam or China, without a customs check. Transit refers to containers being imported into the country, the contents repacked and then re-exported as a new shipment to the destination.

For both China and Vietnam, the top transhipment locations are Singapore and Malaysia. South Korea and Indonesia are also common transhipment countries. Vietnam and Hong Kong are frequent transit hubs for goods to China. In Vietnam, shipments are broken down into smaller batches to be smuggled into China overland.

The Africa to Asia trafficking network

The wildlife trafficking network spanning from West/Central Africa to Asia is complex. Multiple African and Asian nationals are involved, with specialised roles. Poachers, middlemen, transport, shipping and clearance agents in export, transit and destination countries and corrupt government officials at ports, all play a key role along the trade chain.

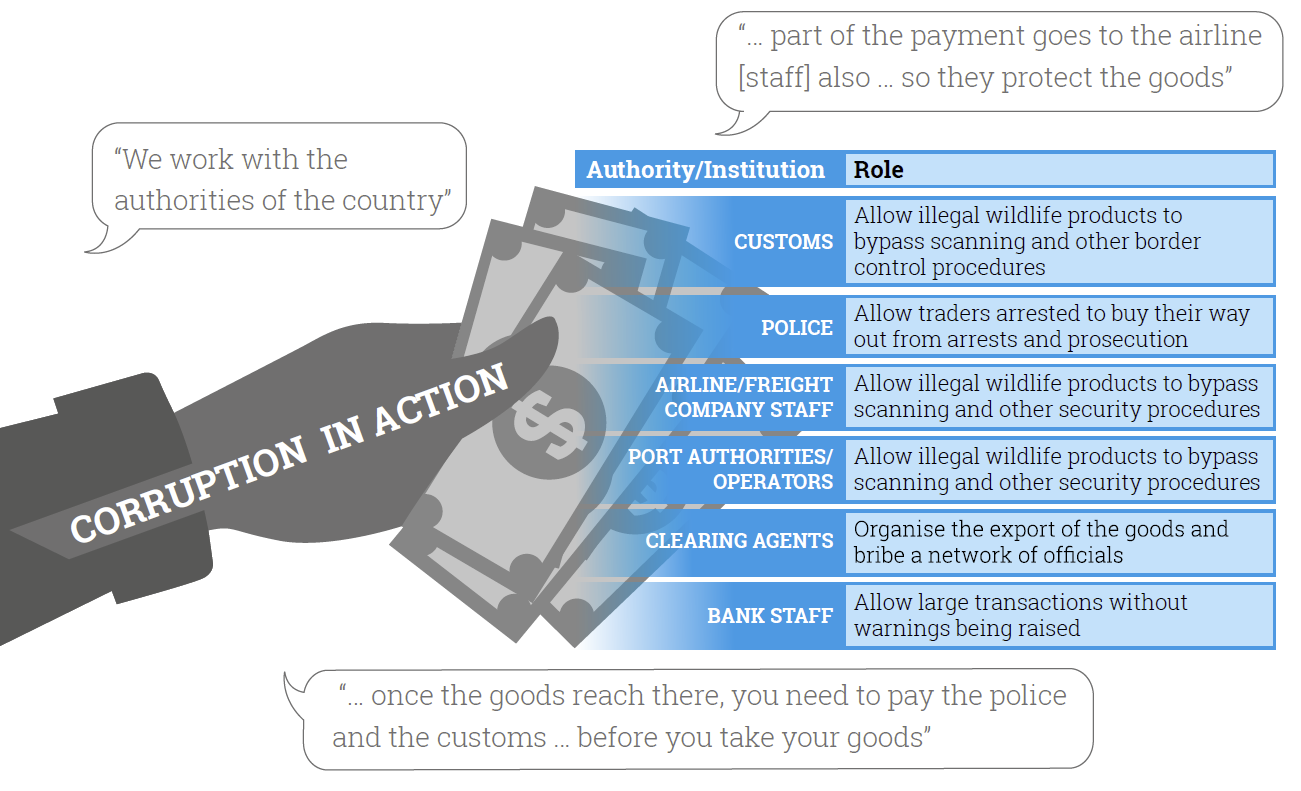

Role of corruption in Nigeria and nearby countries

Traffickers and shipping agents claim that customs officials at border control are often aware of the illegal wildlife goods being moved through their checkpoints.

Up to 70 per cent of the fees charged by corrupt clearing agents are for bribes to government officials and private transport company staff involved in the container scanning process.

Corrupt customs officials demand different levels of bribes to circumvent scanning depending on the goods involved.

Impact of coronavirus pandemic on ivory and pangolin trafficking in West and Central Africa

Lockdown in Nigeria and other countries has equally prevented Vietnamese and Chinese traders, the primary buyers of ivory and pangolin scales, from travelling into the country.

Prior to lockdown, ivory and pangolin scale suppliers would rarely sell to buyers without face-to-face meetings, but EIA information has ascertained that traffickers have adapted their modus operandi by increasingly using online platforms to circumvent pandemic restrictions. demonstrating the flexibility and willingness of criminals to pursue profit in the face of increased risk.

In light of this shift, it is possible that traffickers’ online customer bases will have grown throughout 2020, increasing their potential sales and consequently maintaining pressure on globally threatened wildlife such as elephants and pangolins.

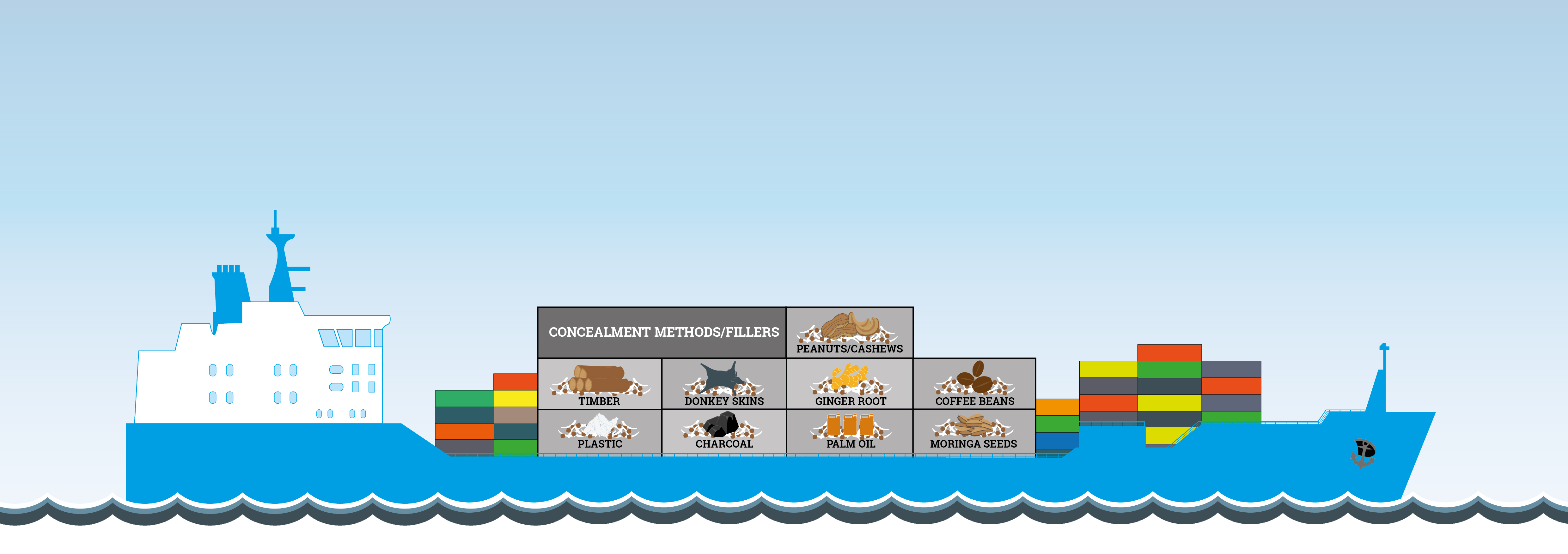

Cashew nuts are commonly used as a ‘filler’ or concealment method for ivory and pangolin scales sent by sea freight from Nigeria to Asia, often exported from Apapa seaport. EIA intelligence suggests that sacks of ivory and pangolin are loaded into shipping containers, tightly surrounded by cashew nut bags as further concealment.

Smugglers use a variety of concealment methods or ‘fillers’ to disguise ivory and pangolin scales, depending on the legality of the filler, costs and whether the filler is similar to the contraband in shape and size.

Conclusion and recommendations

Tap or hover over the items below for recommendations

Lack of political will

Wildlife trafficking should be a matter of national priority due to its role in irreversible biodiversity decline, the spread of zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19, the convergence with other serious crime types, harming economic development and the destabilisation of the rule of law.

Recommendation

Heads of states should prioritise the development and implementation of national strategies to tackle wildlife trafficking.

Lack of law enforcement

A low level of capacity and under-resourced law enforcement agencies, along with a lack of co-operation between relevant national agencies, has hindered a successful criminal justice response to tackling wildlife crime to date.

Recommendation

Undertake intelligence-led investigations co-ordinated by a well-resourced multi-agency enforcement unit/taskforce.

Role of foreign nationals

Foreign criminals, from both neighbouring and other countries in the region, as well as Asian countries such as China, Malaysia and Vietnam, play a key role in sourcing, transporting, consolidating, trafficking and financing ivory and pangolin trafficking.

Recommendation

Utilise existing channels for mutual legal assistance as well as diplomatic and political bilateral dialogues.

Non-compliance within the transport sector

Specialised transporters exploit corruption at key entry/exit points and adopt fraudulent techniques to avoid detection such as using front companies and switching the bill of lading.

Recommendation

Incentivise shipping companies, clearing agents, freight forwarders and other private transport operators.

Weak governance

The majority of countries in West and Central African region have a track record of poor government transparency and accountability as well as the suppression of press and civil society freedoms, which have hindered efforts to counter organised crime and enabled a culture of corruption and non-compliance.

Recommendation

Empower civil society and local community groups.

Out of Africa

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.

Out of Africa

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.