Summary

An estimated 2.9 million whales were killed during the 20th century, leaving global whale populations decimated.

The 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling enacted by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) saved several whale species from extinction and allowed some populations to recover.

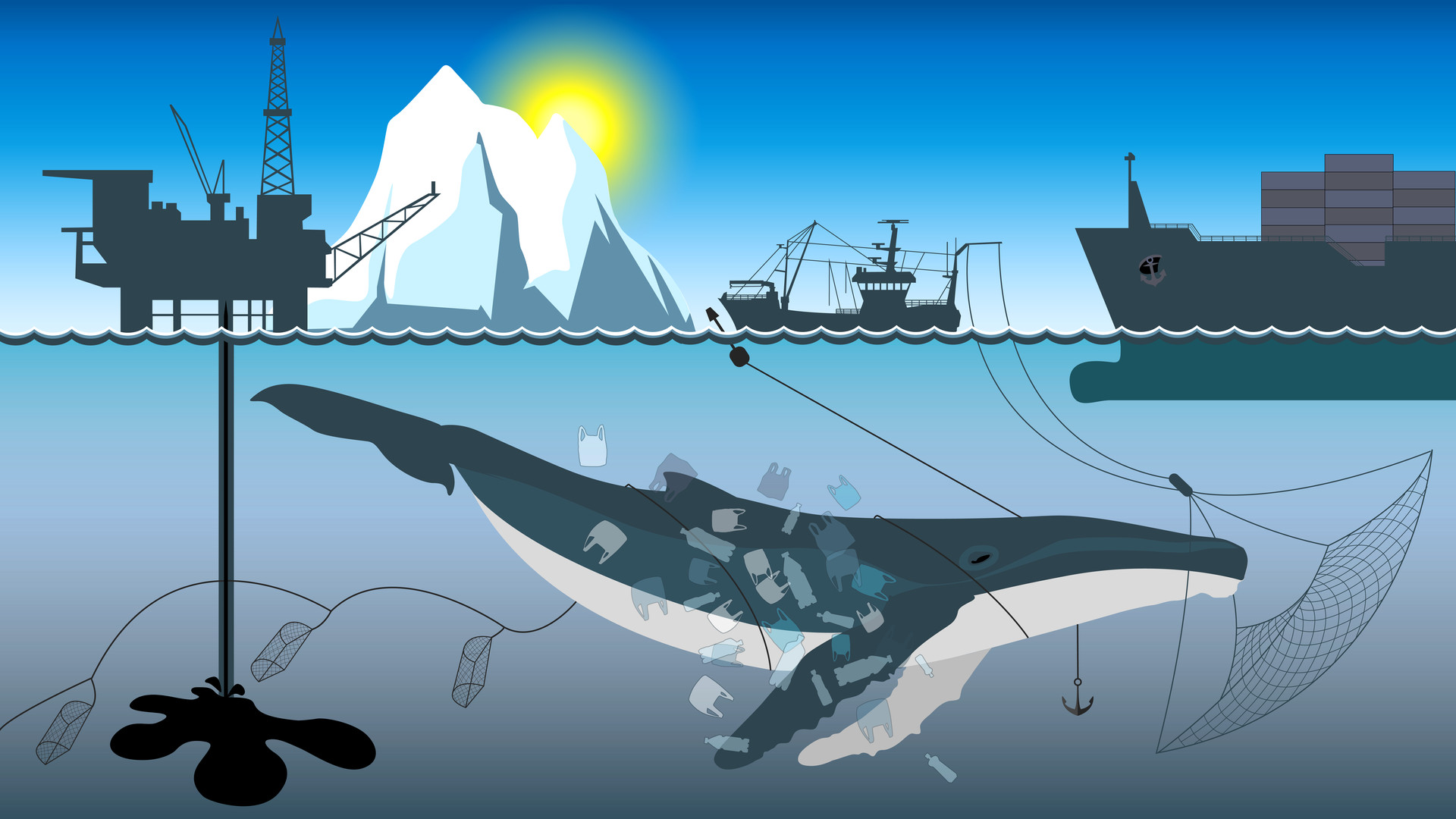

Despite the global ban, Japan, Norway and Iceland continue commercial whaling. Propped up by government subsidies and support, commercial whaling flies in the face of international environmental agreements while serving no economic or nutritional purpose. Furthermore, whales, dolphins and porpoises now face grave and growing threats from a range of additional human activities, from climate change to pollution.

It is time for commercial whaling to end for good. IWC members must strongly reaffirm the continuation of the moratorium and promote to the fullest extent the conservation of all whales.

Summary

An estimated 2.9 million whales were killed during the 20th century, leaving global whale populations decimated.

The 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling enacted by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) saved several whale species from extinction and allowed some populations to recover.

Despite the global ban, Japan, Norway and Iceland continue commercial whaling. Propped up by government subsidies and support, commercial whaling flies in the face of international environmental agreements while serving no economic or nutritional purpose. Furthermore, whales, dolphins and porpoises now face grave and growing threats from a range of additional human activities, from climate change to pollution.

It is time for commercial whaling to end for good. IWC members must strongly reaffirm the continuation of the moratorium and promote to the fullest extent the conservation of all whales.

Commercial whaling - a history of over-exploitation

Commercial whaling - a history of over-exploitation

Since 1986

Norway

Since 1986

Norway

Norway

Before the moratorium took effect, Norway killed an average of 2,000 minke whales a year.

Norway objected to the ban, allowing its commercial whaling industry to continue after 1986. Initially, this was done under the ‘special permit’ provision which allows IWC Contracting Governments to ‘kill, take and treat whales for purposes of scientific research’.

In 1993, Norway resumed commercial whaling under its objection to the moratorium. From an initial catch of 157 minkes in 1993, Norway’s commercial whale hunt peaked with 763 whales killed in 2014. In total, Norway has killed 17,000 minke whales since 1986.

An industry in crisis

Since 2014, the number of vessels engaged in the Norwegian whaling industry has declined and the number of whales killed consistently falls far short of the quotas issued by the government.

The Government acknowledges the problems within the whaling industry but attributes its struggles to a failure to recruit more fishermen into whaling, and to the simple fact that fishing is more profitable.

The market faces a growing glut of whale meat. In 2017, more than 80 pallets of unsold whale meat were given away ‘because stores can only keep the meat for a one year shelf life and this meat is seven- or eight-months-old and hard to sell’.

From 2023, the use of a blue box is no longer a requirement for whaling vessels, meaning that no monitoring of whaling now takes place.

Norway

Before the moratorium took effect, Norway killed an average of 2,000 minke whales a year.

Norway objected to the ban, allowing its commercial whaling industry to continue after 1986. Initially, this was done under the ‘special permit’ provision which allows IWC Contracting Governments to ‘kill, take and treat whales for purposes of scientific research’.

In 1993, Norway resumed commercial whaling under its objection to the moratorium. From an initial catch of 157 minkes in 1993, Norway’s commercial whale hunt peaked with 763 whales killed in 2014. In total, Norway has killed 14,306 minke whales since 1986.

An industry in crisis

Since 2014, the number of vessels engaged in the Norwegian whaling industry has declined and the number of whales killed consistently falls far short of the quotas issued by the government. Only two large processing/distributing companies bought whale meat in 2017, down from five the previous year.

The Government acknowledges the problems within the whaling industry but attributes its struggles to a failure to recruit more fishermen into whaling, and to the simple fact that fishing is more profitable.

The market faces a growing glut of whale meat. In 2017, more than 80 pallets of unsold whale meat were given away ‘because stores can only keep the meat for a one year shelf life and this meat is seven- or eight-months-old and hard to sell’.

Since 1986

Iceland

Since 1986

Iceland

Iceland

Iceland did not formally object to the 1986 moratorium and was thus bound by the ban. However, it continued whaling after the moratorium took effect under the special permit provision. In 1992, the country withdrew from the IWC.

In 2002, Iceland rejoined the IWC and lodged a reservation to the moratorium – a move disputed by many countries as being contrary to international law. Iceland resumed special permit whaling in 2003.

In 2006, the country resumed commercial whaling under its contested reservation to the moratorium, targeting endangered fin whales as well as minke whales.

In June 2018, the Hvalur whaling company resumed fin whaling after a two year hiatus. The company came under intense international criticism in early July, when it killed a rare blue/fin hybrid whale. According to recent tax filings, Hvalur has not made a profit from whaling for some time.

Public support for whaling has plummeted in Iceland. A 2023 survey found that 51 per cent of the population actively oppose it (compared to 18 per cent in 2013).

The damaging climate, economic, welfare and biodiversity impacts of Iceland’s fin whaling are uncovered by EIA in 2023.

MASTS uncovered the cruelty of fin whaling in 2023, and the Icelandic government responded by issuing a temporary ban on whaling.

Despite increasing and vocal national and international opposition, in June 2024 Iceland’s Government wasted an opportunity to pull the plug and issued a new one-year licence to hunt threatened fin whales.

Iceland

Iceland did not formally object to the 1986 moratorium and was thus bound by the ban. However, it continued whaling after the moratorium took effect under the special permit provision. In 1992, the country withdrew from the IWC.

In 2002, Iceland rejoined the IWC and lodged a reservation to the moratorium – a move disputed by many countries as being contrary to international law. Iceland resumed special permit whaling in 2003.

In 2006, the country resumed commercial whaling under its contested reservation to the moratorium, targeting endangered fin whales as well as minke whales.

In June 2018, the Hvalur whaling company resumed fin whaling after a two year hiatus. The company came under intense international criticism in early July, when it killed a rare blue/fin hybrid whale. According to recent tax filings, Hvalur has not made a profit from whaling for some time.

Public support for whaling has plummeted in Iceland. A 2018 survey found that 34 per cent of the population actively oppose it (compared to 18 per cent in 2013).

Opposition has extended to Iceland’s parliament, with a number of MPs calling for a review of the reputational impact of Iceland’s whaling policy on key sectors such as tourism, and to assess the economic contribution of whaling compared to other sectors. The review is underway.

Norway and Iceland: A failure to apply a precautionary approach

Following the adoption of the moratorium, the IWC asked its Scientific Committee to develop a precautionary approach to setting commercial whaling quotas in the event that the moratorium was ever lifted. The Scientific Committee offered a range of possible tuning levels to the IWC, from the least conservative (.60) to the more precautionary (.72).

Norway initially set its quotas using the .72 tuning level but switched to a .66 level in 2003 to avoid having to greatly reduce its whaling quotas due to the higher-than-average proportion of female minke whales being killed. In 2005, the tuning level was further dropped to .60, despite concerns raised by the IWC. Iceland’s 2018 fin whale quota is the highest since its resumption of commercial whaling

Based on a series of marine surveys since 1986, it is apparent that there have been considerable changes in the distribution and abundance of several cetacean species in Icelandic waters. Minke whales in particular have suffered a statistically significant decline. Norwegian researchers have also seen declines in minke whale abundance.

Norway and Iceland: A failure to apply a precautionary approach

Following the adoption of the moratorium, the IWC asked its Scientific Committee to develop a precautionary approach to setting commercial whaling quotas in the event that the moratorium was ever lifted. The Scientific Committee offered a range of possible tuning levels to the IWC, from the least conservative (.60) to the more precautionary (.72).

Norway initially set its quotas using the .72 tuning level but switched to a .66 level in 2003 to avoid having to greatly reduce its whaling quotas due to the higher-than-average proportion of female minke whales being killed. In 2005, the tuning level was further dropped to .60, despite concerns raised by the IWC. Iceland’s 2018 fin whale quota is the highest since its resumption of commercial whaling

Based on a series of marine surveys since 1986, it is apparent that there have been considerable changes in the distribution and abundance of several cetacean species in Icelandic waters. Minke whales in particular have suffered a statistically significant decline. Norwegian researchers have also seen declines in minke whale abundance.

Since 1986

Japan

Since 1986

Japan

Japan

Japan initially filed an objection to the moratorium and continued commercial hunting. Following intense pressure from the United States and a threatened loss of fishing access, Japan signed the Murazawa-Baldrige deal in 1987 and subsequently became bound to the global ban.

Immediately after this, the Japanese Government began issuing special permits for lethal research – initially in the Antarctic, and later in the North Pacific too. The country’s ‘scientific’ whaling has been repeatedly criticised by scientists, governments and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), as well as by the IWC itself.

In 2010, Australia initiated proceedings against Japan through the ICJ, claiming that its Antarctic whaling programme was in breach of its obligations under international agreements. In 2014, the ICJ ruled that the special permits issued by Japan for the killing, taking and treating of whales were not granted ‘for purposes of scientific research’.

Although Japan initially complied with the ICJ ruling and suspended its hunt, it quickly replaced the condemned research programme with another, which proposed to kill up to 333 minke whales a year until 2027.

The Japanese Government has remained outspoken in its support for commercial whaling. The fisheries agency launched a new whaling ‘mothership’, the Kangei Maru, in spring 2024, despite 85 per cent of Japanese citizens opposing the use of taxpayer yen to build a new factory ship.

Although viewed as the main market globally for edible whale products, whale meat is not commonly eaten in Japan. At least 3,500 supermarkets, including major chains such as AEON, Ito-Yokado and Seiyu, have stopped selling whale and dolphin products in Japan.

In July 2024, the Japanese Fisheries Agency issued a new commercial quota to hunt 59 North Pacific fin whales a year, against international law. The whale meat from the hunt, which began in early August, is processed and stored aboard the Kangei Maru, a new factory ship costing 7.5 billion yen (~US$47 million) that was launched in May 2024.

Japan

Japan initially filed an objection to the moratorium and continued commercial hunting. Following intense pressure from the United States and a threatened loss of fishing access, Japan signed the Murazawa-Baldrige deal in 1987 and subsequently became bound to the global ban.

Immediately after this, the Japanese Government began issuing special permits for lethal research – initially in the Antarctic, and later in the North Pacific too. The country’s ‘scientific’ whaling has been repeatedly criticised by scientists, governments and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), as well as by the IWC itself.

In 2010, Australia initiated proceedings against Japan through the ICJ, claiming that its Antarctic whaling programme was in breach of its obligations under international agreements. In 2014, the ICJ ruled that the special permits issued by Japan for the killing, taking and treating of whales were not granted ‘for purposes of scientific research’.

Although Japan initially complied with the ICJ ruling and suspended its hunt, it quickly replaced the condemned research programme with another, which proposed to kill up to 333 minke whales a year until 2027.

The Japanese Government has remained outspoken in its support for commercial whaling. The fisheries agency committed $900,000 to a study into replacing the 30-year-old whaling ‘mothership’ despite 85 per cent of Japanese citizens opposing the use of taxpayer yen to build a new factory ship.

Although viewed as the main market globally for edible whale products, whale meat is not commonly eaten in Japan. At least 3,500 supermarkets, including major chains such as AEON, Ito-Yokado and Seiyu, have stopped selling whale and dolphin products in Japan.

Problematic trade

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) has banned international commercial trade in the products of endangered whale species. While trade among Iceland, Japan and Norway is technically legal since the countries hold reservations to the ban, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre has raised concerns that such sizeable levels of trade undermine the effectiveness of established protections.

Japan, Iceland and Norway all have specific health requirements relevant to the sale of edible whale products. The failure to meet these requirements, both domestic and foreign, has been a common hindrance to Iceland and Norway’s whale product trade.

There have also been problems with the DNA registries used for traceability purposes.

Problematic trade

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) has banned international commercial trade in the products of endangered whale species. While trade among Iceland, Japan and Norway is technically legal since the countries hold reservations to the ban, the United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre has raised concerns that such sizeable levels of trade undermine the effectiveness of established protections.

Japan, Iceland and Norway all have specific health requirements relevant to the sale of edible whale products. The failure to meet these requirements, both domestic and foreign, has been a common hindrance to Iceland and Norway’s whale product trade.

There have also been problems with the DNA registries used for traceability purposes.

Going to the dogs

In an increasingly desperate search for profits, all three nations whaling for commercial purposes have looked to the production of feed for animals.

In 2016, it was reported that the Norwegian company Rogaland Pelsdyrfôrlag used more than 113 tonnes of dumped whale products as food for fur animals.

Going to the dogs

In an increasingly desperate search for profits, all three nations whaling for commercial purposes have looked to the production of feed for animals.

In 2016, it was reported that the Norwegian company Rogaland Pelsdyrfôrlag used more than 113 tonnes of dumped whale products as food for fur animals.

Further threats

Since the 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling came into force, whales have come under unprecedented and mounting pressure.

Further threats

Since the 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling came into force, whales have come under unprecedented and mounting pressure.

Inhumane

There remain significant welfare concerns regarding the methods of all three countries engaged in whaling for commercial purposes.

In 2023, a report by the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority (MAST) provided clear and damning evidence of the suffering experienced by fin whales, the world’s fastest and second-largest whale species. It documented incidents in which whales hit with explosive harpoons took up to two hours to die, as well as the slaughter of pregnant and lactating females.

Iceland has collected very limited data on time to death (TTD) rates for minke whales killed. Although TTD data collected in 2014 claimed that 42 died ‘instantly’ (defined by the IWC as within 10 seconds of being shot), the remaining eight whales had to be shot a second time and their median TTD was eight minutes.

Norway recently collected TTD data for 271 minke whales. The median TTD for the 49 whales not registered as instantaneous deaths was six minutes. One whale had to be shot twice, taking 20-25 minutes to die.

Japan has not submitted welfare data to the IWC since 2006 but provides reports to the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). Minke whales taken in the offshore North Pacific hunt take an average of two minutes to die, while those in the coastal hunt take over five minutes. Antarctic minkes take an average of 1.8 minutes to die.

Inhumane

There remain significant welfare concerns regarding the methods of all three countries engaged in whaling for commercial purposes.

Iceland has collected very limited data on time to death (TTD) rates for minke whales killed. Although TTD data collected in 2014 claimed that 42 died ‘instantly’ (defined by the IWC as within 10 seconds of being shot), the remaining eight whales had to be shot a second time and their median TTD was eight minutes.

Norway recently collected TTD data for 271 minke whales. The median TTD for the 49 whales not registered as instantaneous deaths was six minutes. One whale had to be shot twice, taking 20-25 minutes to die.

Japan has not submitted welfare data to the IWC since 2006 but provides reports to the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). Minke whales taken in the offshore North Pacific hunt take an average of two minutes to die, while those in the coastal hunt take over five minutes. Antarctic minkes take an average of 1.8 minutes to die. Since 2023, Norwegian whaling vessels no longer have any monitoring data collected.

Ecosystem engineers

A growing body of scientific research demonstrates that whales enhance marine ecosystems in several ways (mouseover/tap the images to find out how):

The ‘whale pump’

By releasing faecal plumes and diving to feed, whales transfer important nutrients such as nitrogen and iron to surface waters. This ‘whale pump’ function plays a role in enhancing marine productivity.

Nutrient recycling

Gray and humpback whales disturb the sea bottom to feed, causing substantial amounts of sediment and nutrients to become suspended in the water column. This causes nutrient recycling and brings crustaceans to the ocean surface, providing nourishment for seabirds.

The ‘great whale conveyor belt’

As large whales migrate, they free nutrients for drifting phytoplankton – the base of the food web upon which all fish stocks rely.

Organic enrichment

When whales die their massive bodies sequester significant amounts of carbon and provide massive pulses of organic enrichment, including proteins and lipids, to the sea floor, an area often impoverished in nutrients and energy.

Ecosystem engineers

A growing body of scientific research demonstrates that whales enhance marine ecosystems in several ways (mouseover/tap the images to find out how):

The ‘whale pump’

By releasing faecal plumes and diving to feed, whales transfer important nutrients such as nitrogen and iron to surface waters. This ‘whale pump’ function plays a role in enhancing marine productivity.

Nutrient recycling

Gray and humpback whales disturb the sea bottom to feed, causing substantial amounts of sediment and nutrients to become suspended in the water column. This causes nutrient recycling and brings crustaceans to the ocean surface, providing nourishment for seabirds.

The ‘great whale conveyor belt’

As large whales migrate, they free nutrients for drifting phytoplankton – the base of the food web upon which all fish stocks rely.

Organic enrichment

When whales die their massive bodies sequester significant amounts of carbon and provide massive pulses of organic enrichment, including proteins and lipids, to the sea floor, an area often impoverished in nutrients and energy.

Recommendations

It is time to fully consign commercial whaling to the history books.

We call on IWC Contracting Governments to take the following steps:

- Strongly support action within the IWC to strengthen the moratorium on commercial whaling and advance the conservation of all cetaceans

- Firmly reject any proposals that seek to undermine the moratorium on commercial whaling, including resolutions aimed towards lifting the moratorium and development of the whaling industry

- Support increased efforts to expand IWC’s cooperation with other intergovernmental organisations

- Contracting Governments should financially support to the IWC in order to strengthen the valuable work of the Scientific Committee and the Conservation Committee

- Ensure the IWC’s limited research budget prioritises efforts to enhance the conservation of whales, dolphins and porpoises.

- Lead and support communications and outreach to persuade Japan, Norway and Iceland to abide by the moratorium on commercial whaling

- Engage with CITES Parties in reaffirming the importance of the Appendix I listings for great whales and ensure robust enforcement of the international ban on trade in whale products

- Support domestic and international policies and agreements that seek to strengthen marine conservation measures and non-lethal utilisation of cetaceans, including eco-tourism and whale-watching

- Support projects in countries which strengthen cetacean research and conservation efforts.

Recommendations

It is time to fully consign commercial whaling to the history books.

We call on IWC Contracting Governments to take the following steps:

- Strongly support action within the IWC to strengthen the moratorium on commercial whaling and advance the conservation of all cetaceans.

- Firmly reject any proposals that seek to undermine the moratorium on commercial whaling, including Japan’s package of documents related to the Way Forward of the IWC

- Ensure the IWC’s limited research budget prioritises efforts to enhance the conservation of whales, dolphins and porpoises.

- Lead and support communications and outreach to persuade Japan, Norway and Iceland to abide by the moratorium on commercial whaling

- Engage with CITES Parties in reaffirming the importance of the Appendix I listings for great whales and ensure robust enforcement of the international ban on trade in whale products

- Support domestic and international policies and agreements that seek to strengthen marine conservation measures and non-lethal utilisation of cetaceans, including eco-tourism and whale-watching

- Support projects in countries which strengthen cetacean research and conservation efforts.

End commercial whaling:

Reinforce the IWC’s Global Moratorium to Protect Cetaceans in the 21st Century

Download the briefing to the 69th Meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC).

Commercial whaling:

Unsustainable, Inhumane, Unnecessary

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.

End commercial whaling:

Reinforce the IWC’s Global Moratorium to Protect Cetaceans in the 21st Century

Download the briefing to the 69th Meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC).

Commercial whaling:

Unsustainable, Inhumane, Unnecessary

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.