Summary

A review and analysis of survey, HFC Registry and customs data alongside widespread media reports indicates that Europe is faced with a substantial level of illegal use and trade in HFCs.

EIA’s analysis of 2018 customs data suggests that as much as 16.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) of bulk HFCs were illegally placed on the market in 2018. This represents more than 16% of the 2018 quota and is in addition to illegal imports of HFC-containing equipment and illegal HFCs that are undoubtedly being smuggled under the radar of customs.

Illegal trade of HFCs undermines the F-gas Regulation, results in additional HFC emissions that fuel global warming and significantly reduces government income and the profits of legitimate businesses. We are concerned that the illegal trade along with stockpiling of HFCs in 2017 has produced a false sense of security in terms of availability of HFCs to meet the phase-down steps from 2018 onwards. Future quota cuts will be difficult to meet unless the transition to low-GWP alternatives is accelerated.

Summary

A review and analysis of survey, HFC Registry and customs data alongside widespread media reports indicates that Europe is faced with a substantial level of illegal use and trade in HFCs.

EIA’s analysis of 2018 customs data suggests that as much as 16.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) of bulk HFCs were illegally placed on the market in 2018. This represents more than 16% of the 2018 quota and is in addition to illegal imports of HFC-containing equipment and illegal HFCs that are undoubtedly being smuggled under the radar of customs.

Illegal trade of HFCs undermines the F-gas Regulation, results in additional HFC emissions that fuel global warming and significantly reduces government income and the profits of legitimate businesses. We are concerned that the illegal trade along with stockpiling of HFCs in 2017 has produced a false sense of security in terms of availability of HFCs to meet the phase-down steps from 2018 onwards. Future quota cuts will be difficult to meet unless the transition to low-GWP alternatives is accelerated.

History of HFCs

History of HFCs

Customs Data

2018 Customs Data Analysis

Customs data for 2018 indicates significant over-supply of HFCs to the European market. Bulk HFC imports fell in 2018 compared to 2017 but increased compared to 2016.

Through a detailed analysis of European import and export data, EIA estimates that as much as 117.5 MtCO2e of HFCs were placed on the market in 2018 through bulk imports. This is some 16.3 MtCO2e above the available quota of 101.2 MtCO2e, more than 16% over the allowable quota.

There is a worrying trend of significantly increased imports over 2016-2018 in a number of countries, despite the significant cut in HFC quota in 2018 of 37% from the baseline. This could indicate illegal trade hotspots.

Increase in CO2e-weighted HFC imports from 2016-2018 in various EU countries

Comparison of customs data with reported data

EIA’s analysis indicates a discrepancy between European customs data and data reported by companies to the HFC Registry.

According to European customs data 2016 bulk imports were lower than those reported to the HFC Registry by 2,557 tonnes, while in 2017 the imports according to the European customs data are higher by 728 tonnes. However, if the CO2e of the imports are calculated, based on the GWPs of the reported CN codes, the discrepancy between the two sets of data is much higher in 2017 than in 2016. Calculated on a CO2e basis, in 2017 European customs data indicates HFC imports of 166.58 MtCO2e, 12.1 MtCO2e higher than the HFC Registry data.

Taking the import and export data together, the European customs data indicates that a significantly higher amount of HFCs (5,527 tonnes) was placed on the European market in 2017 than reported to the HFC Registry. In CO2e terms, the discrepancy is 14.8 MtCO2e, equivalent to 8.7% of the total quota.

It is clear from the data that significant stockpiling took place in 2017 in preparation for the 2018 cut.

Given that reports to the HFC Registry are self-declared and there is limited or no cross-checking with customs data, there is great potential for manipulation of HFC Registry reported data.

Bulk HFC imports to the EU as a whole were 21% higher in 2017 than in 2016

Customs Data

2018 Customs Data Analysis

Customs data for 2018 indicates significant over-supply of HFCs to the European market. Bulk HFC imports fell in 2018 compared to 2017 but increased compared to 2016.

Through a detailed analysis of European import and export data, EIA estimates that as much as 117.5 MtCO2e of HFCs were placed on the market in 2018 through bulk imports. This is some 16.3 MtCo2e above the available quota of 101.2 MtCO2e, more than 16% over the allowable quota.

There is a worrying trend of significantly increased imports over 2016-2018 in a number of countries, despite the significant cut in HFC quota in 2018 of 37% from the baseline. This could indicate illegal trade hotspots.

Increase in CO2e-weighted HFC imports from 2016-2018 in various EU countries

Comparison of customs data with reported data

EIA’s analysis indicates a discrepancy between European customs data and data reported by companies to the HFC Registry.

According to European customs data 2016 bulk imports were lower than those reported to the HFC Registry by 2,557 tonnes, while in 2017 the imports according to the European customs data are higher by 728 tonnes. However, if the CO2e of the imports are calculated, based on the GWPs of the reported CN codes, the discrepancy between the two sets of data is much higher in 2017 than in 2016. Calculated on a CO2e basis, in 2017 European customs data indicates HFC imports of 166.58 MtCO2e, 12.1 MtCO2e higher than the HFC Registry data.

Taking the import and export data together, the European customs data indicates that a significantly higher amount of HFCs (5,527 tonnes) was placed on the European market in 2017 than reported to the HFC Registry. In CO2e terms, the discrepancy is 14.8 MtCO2e, equivalent to 8.7% of the total quota.

It is clear from the data that significant stockpiling took place in 2017 in preparation for the 2018 cut.

Given that reports to the HFC Registry are self-declared and there is limited or no cross-checking with customs data, there is great potential for manipulation of HFC Registry reported data.

Bulk HFC imports to the EU as a whole were 21% higher in 2017 than in 2016

HFC prices

HFC prices in Europe began seriously rising in 2017 in anticipation of the 2018 HFC quota cut. By the second quarter of 2018, the price of HFC-410A was 859% higher for Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and 833% higher for service companies than in 2014. Similar prices hikes have been seen for other HFCs, with the highest price increases for those with the highest GWP.

According to the latest Öko-Recherche report, prices in 2018 have flattened out to a large extent and demand for refrigerants, despite the large quota cut, was said to be low. Potential reasons for this include stockpiling in previous quarters (i.e. in 2017), increased care in handling refrigerants, reduced demand due to transitions to lower GWP technologies and possible illegal trade.

HFC prices

HFC prices in Europe began seriously rising in 2017 in anticipation of the 2018 HFC quota cut. By the second quarter of 2018, the price of HFC-410A was 859% higher for Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and 833% higher for service companies than in 2014. Similar prices hikes have been seen for other HFCs, with the highest price increases for those with the highest GWP.

According to the latest Öko-Recherche report, prices in 2018 have flattened out to a large extent and demand for refrigerants, despite the large quota cut, was said to be low. Potential reasons for this include stockpiling in previous quarters (i.e. in 2017), increased care in handling refrigerants, reduced demand due to transitions to lower GWP technologies and possible illegal trade.

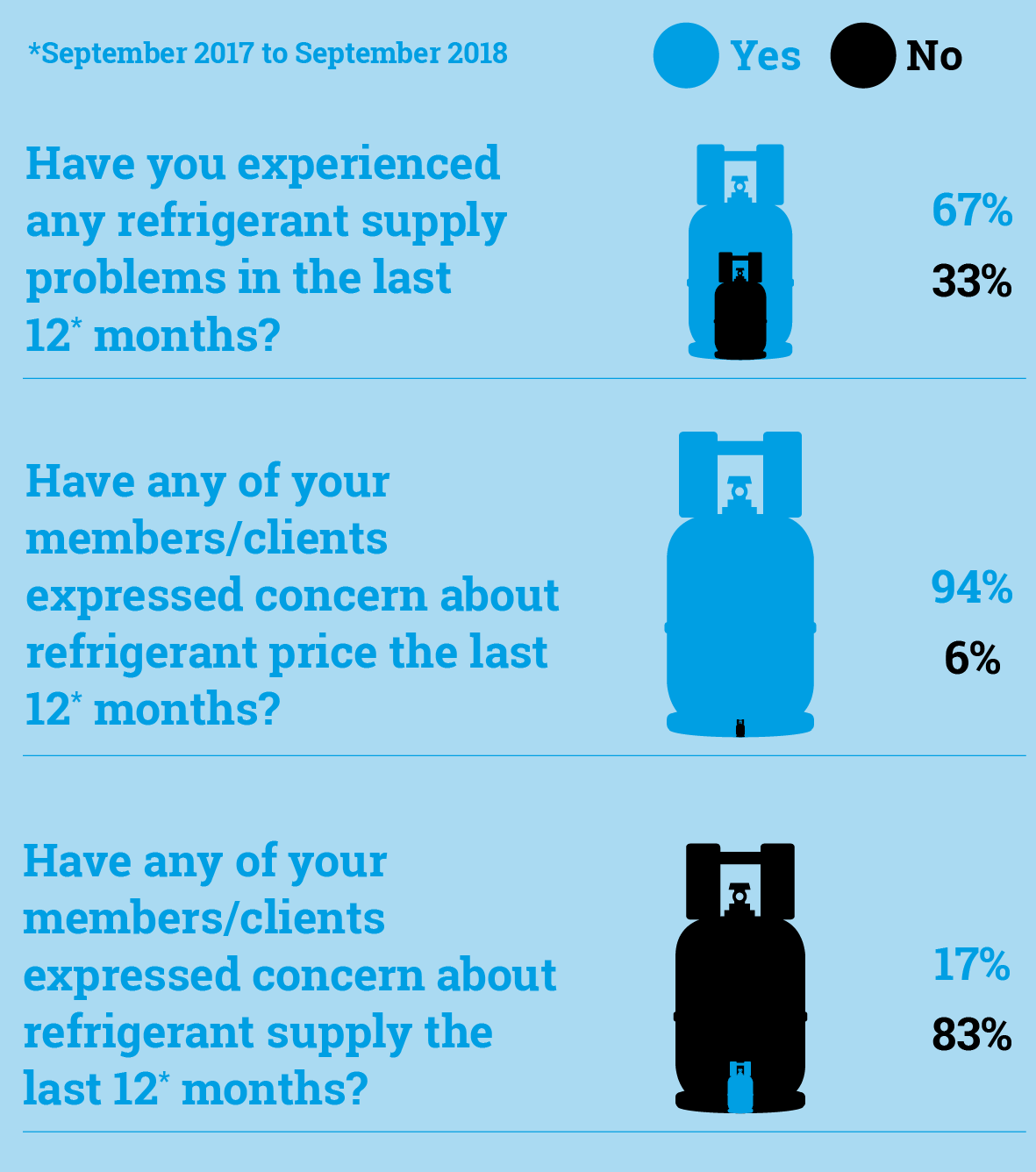

EIA Industry Survey

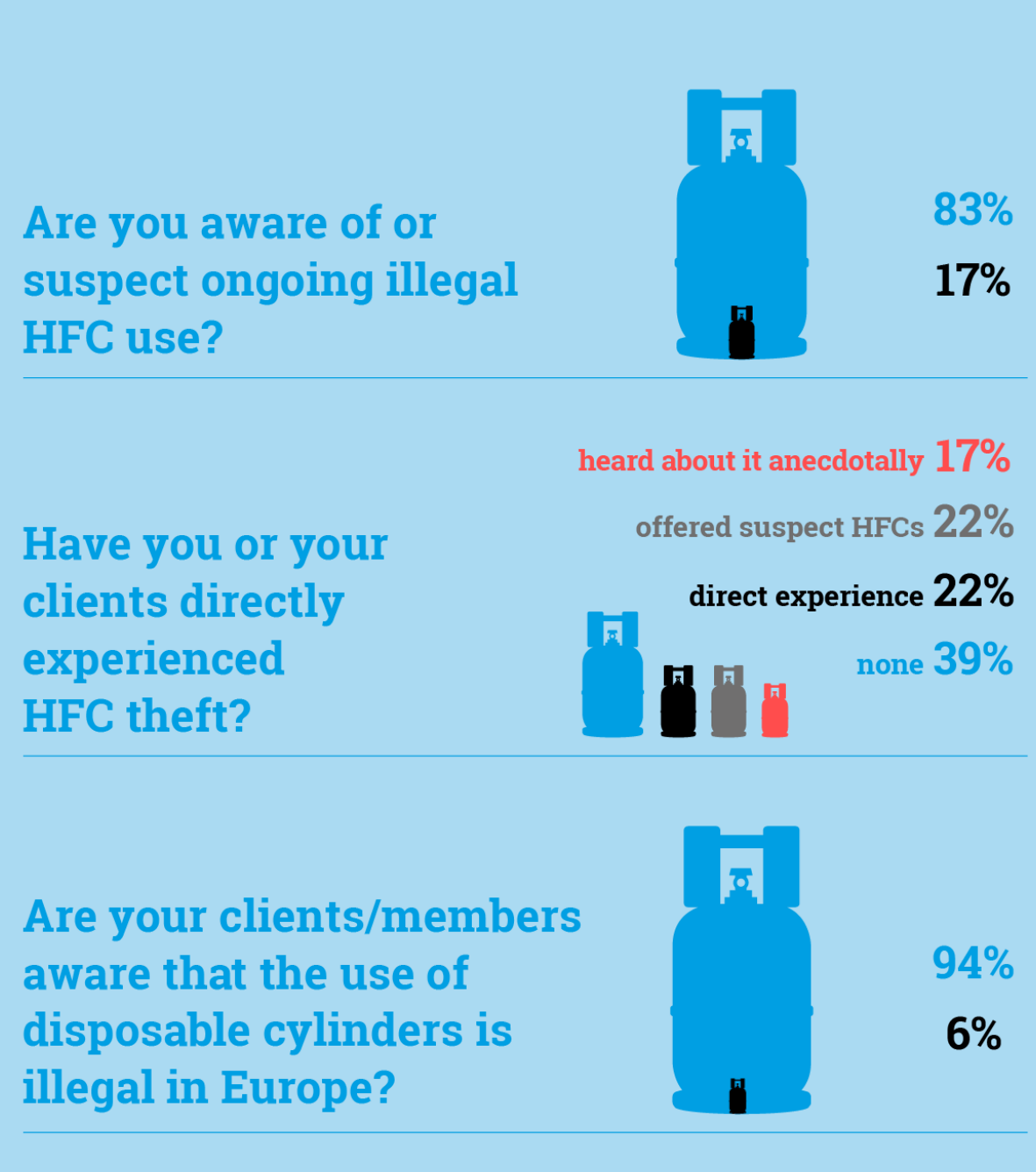

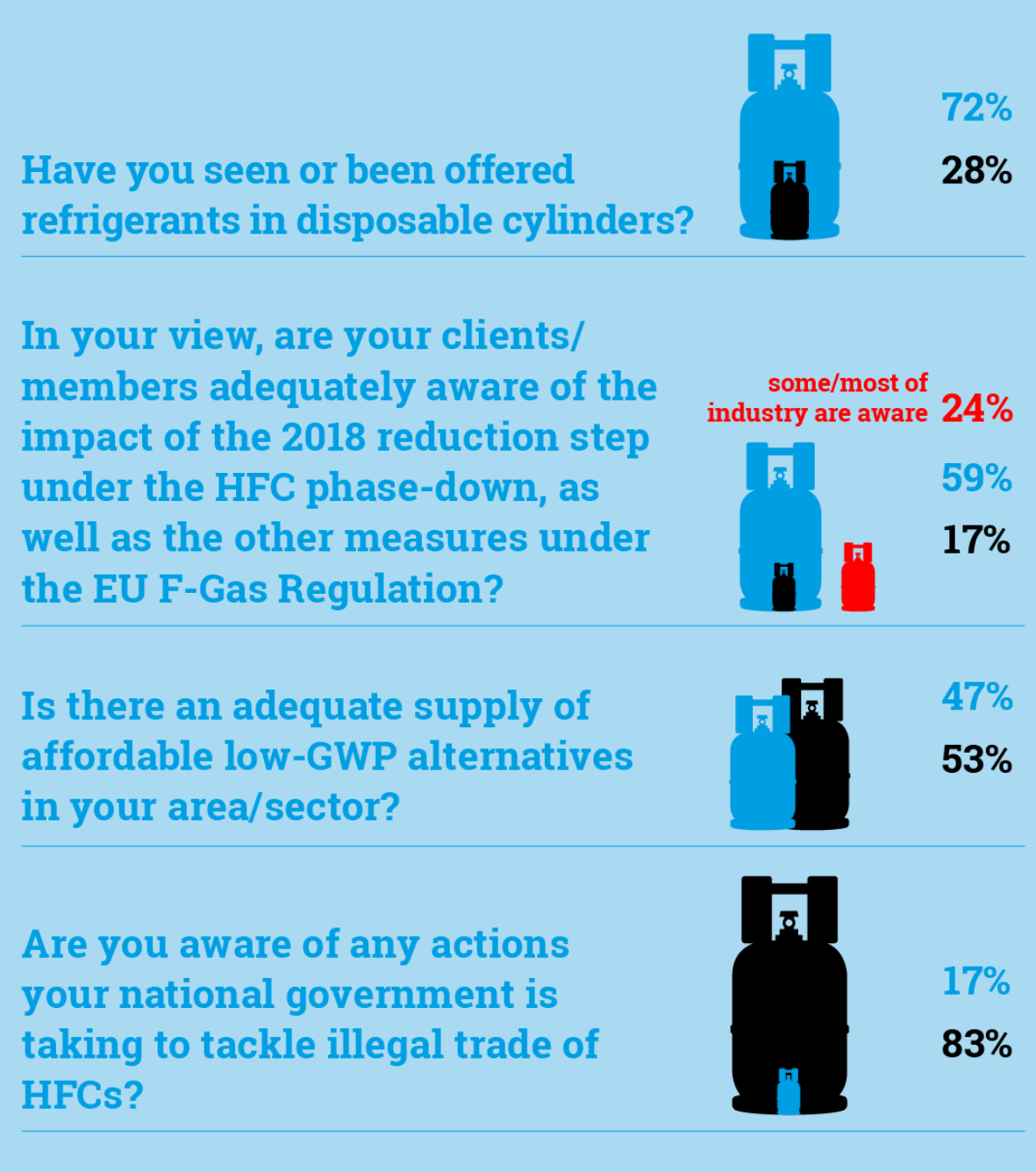

In September and October 2018, we sent a questionnaire to a range of heating, ventilation, air-conditioning and refrigeration (HVACR) representatives, including industry associations, refrigerant suppliers and contractor associations.

The survey requested information on refrigerant prices, the scale and severity of illegal HFC use, potential drivers of illegal trade, awareness of current penalty regimes in member states and recommendations for improving enforcement of the F-gas Regulation. Responses were received from 18 companies, primarily refrigerant suppliers and industry associations, in 11 EU member states.

EIA Industry Survey

The survey requested information on refrigerant prices, the scale and severity of illegal HFC use, potential drivers of illegal trade, awareness of current penalty regimes in member states and recommendations for improving enforcement of the F-gas Regulation. Responses were received from 18 companies, primarily refrigerant suppliers and industry associations, in 11 EU member states.

In September and October 2018, we sent a questionnaire to a range of heating, ventilation, air-conditioning and refrigeration (HVACR) representatives, including industry associations, refrigerant suppliers and contractor associations.

Illegal trade

Information from industry stakeholders alongside media reports and trade data analysis suggests a growing prevalence of illegal HFC trade across the EU.

HFCs are coming into Europe from China directly and via EU-border countries, in particular via Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Albania. Customs data discrepancies indicate key entry points are likely Denmark, Greece, Latvia, Poland and Malta, however all member states need to take steps to examine customs data in relation to company data in the HFC Registry.

Multiple industry sources reported that illegal refrigerants constituted 50-80% of the Greek, Bulgarian and Romanian markets.

In Italy, ~5-10% of the mobile air-conditioning HFC market is estimated to be illegal while in Poland the number is estimated at 30%.

There is an urgent need to immediately improve enforcement of the F-Gas Regulation, particularly at the EU border level. Member states need to seize, prosecute and apply sufficiently high penalties. Penalties that have been determined by member states are generally not high enough to deter HFC smuggling and are rarely applied.

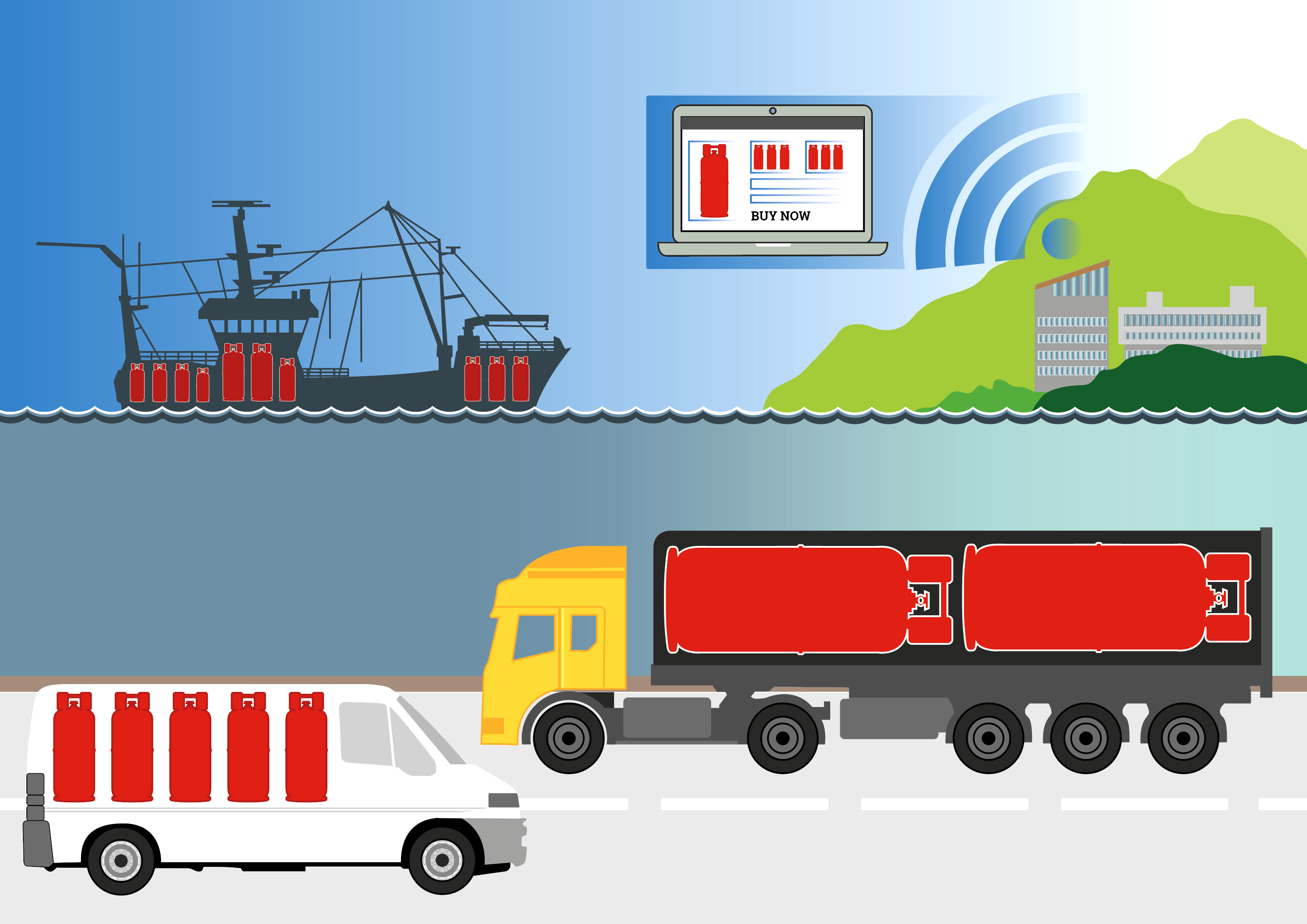

The map illustrates potential trade routes for smuggled HFCs according to industry reports and intelligence gathered by EIA. Illegal HFCs are reportedly entering the EU from Russia and Ukraine in the north-east and from Turkey and Albania in the south-east. Poland has been repeatedly highlighted as a first point of import for illegal HFCs entering the EU.

Illegal trade

Information from industry stakeholders alongside media reports and trade data analysis suggests a growing prevalence of illegal HFC trade across the EU.

HFCs are coming into Europe from China directly and via EU-border countries, in particular via Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Albania. Customs data discrepancies indicate key entry points are likely Denmark, Greece, Latvia, Poland and Malta, however all member states need to take steps to examine customs data in relation to company data in the HFC Registry.

Multiple industry sources reported that illegal refrigerants constituted 50-80% of the Greek, Bulgarian and Romanian markets.

In Italy, ~5-10% of the mobile air-conditioning HFC market is estimated to be illegal while in Poland the number is estimated at 30%.

There is an urgent need to immediately improve enforcement of the F-Gas Regulation, particularly at the EU border level. Member states need to seize, prosecute and apply sufficiently high penalties. Penalties that have been determined by member states are generally not high enough to deter HFC smuggling and are rarely applied.

The map illustrates potential trade routes for smuggled HFCs according to industry reports and intelligence gathered by EIA. Illegal HFCs are reportedly entering the EU from Russia and Ukraine in the north-east and from Turkey and Albania in the south-east. Poland has been repeatedly highlighted as a first point of import for illegal HFCs entering the EU.

Methods of illegal trade

There are two distinct mechanisms with respect to the illegal trade of HFCs in the EU. The first is where companies import non-quota HFCs though the normal customs channels. EIA’s analysis of 2018 customs data suggests that as much as 16.3 MtCO2e of bulk HFCs were illegally placed on the market in this way in 2018 and more than 14.8 MtCO2e in 2017.

The second mechanism, which is much harder to quantify, is the more traditional smuggling of HFCs across borders. This can occur outside customs channels altogether, or where HFCs are concealed either physically or through fraudulent documentation (e.g. mislabelling the type, purpose or destination of the HFC shipment). The significant discrepancies between Chinese export and European import data could be an indication of fraudulent import declarations.

Methods of illegal trade

There are two distinct mechanisms with respect to the illegal trade of HFCs in the EU. The first is where companies import non-quota HFCs though the normal customs channels. EIA’s analysis of 2018 customs data suggests that as much as 16.3 MtCO2e of bulk HFCs were illegally placed on the market in this way in 2018 and more than 14.8 MtCO2e in 2017.

The second mechanism, which is much harder to quantify, is the more traditional smuggling of HFCs across borders. This can occur outside customs channels altogether, or where HFCs are concealed either physically or through fraudulent documentation (e.g. mislabelling the type, purpose or destination of the HFC shipment). The significant discrepancies between Chinese export and European import data could be an indication of fraudulent import declarations.

Regulatory loopholes and tools

Currently the European Commission is not generally obliged to cross check self-declared data reported to the HFC Registry with EU customs data.

Customs officials have access to the HFC Registry where they can check whether or not an importer is registered and access the importer’s annual quota allocation or authorisation. However, there is no access to information that can tell customs how much a company has already imported. Even if an importer is clearly importing an amount in excess of the company’s annual quota (e.g. in one shipment), customs are still not able to determine that the shipment is in contravention of the F-gas Regulation since the importer could claim (legitimately or otherwise) that part of the shipment is for re-export outside the Union.

The current system is inadequate to confirm the legitimacy of new entrants and to prevent them from importing in excess of quota. Companies can simply shut down to avoid repercussions, or mis-declare data to the HFC Registry.

Single Administrative Document (SAD)

HFC Licensing

The EU’s Import Control System (ICS)

Informal Prior Informed Consent (iPIC)

Non-Refillable Containers

(Click images for details)

Regulatory loopholes and tools

Currently the European Commission is not generally obliged to cross check self-declared data reported to the HFC Registry with EU customs data.

Customs officials have access to the HFC Registry where they can check whether or not an importer is registered and access the importer’s annual quota allocation or authorisation. However, there is no access to information that can tell customs how much a company has already imported. Even if an importer is clearly importing an amount in excess of the company’s annual quota (e.g. in one shipment), customs are still not able to determine that the shipment is in contravention of the F-gas Regulation since the importer could claim (legitimately or otherwise) that part of the shipment is for re-export outside the Union.

The current system is inadequate to confirm the legitimacy of new entrants and to prevent them from importing in excess of quota. Companies can simply shut down to avoid repercussions, or mis-declare data to the HFC Registry.

Single Administrative Document (SAD)

HFC Licensing

The EU’s Import Control System (ICS)

Informal Prior Informed Consent (iPIC)

Non-Refillable Containers

(Click images for details)

Lost Profits Due to Illegal HFC Trade

Governments are losing considerable tax revenues due to the illegal HFC trade, through direct loss of VAT and import duty, but also through the indirect impact that illegal trade has to lower the price of legal refrigerants. A recent report from Polish NGO PROZON estimated that Poland’s treasury lost €7 million in 2018 due to illegal refrigerant imports valued at €55 million. Losses to the Lithuanian and Greek exchequers have been estimated at €5 million and €20 million respectively.

Lost Profits Due to Illegal HFC Trade

Governments are losing considerable tax revenues due to the illegal HFC trade, through direct loss of VAT and import duty, but also through the indirect impact that illegal trade has to lower the price of legal refrigerants. A recent report from Polish NGO PROZON estimated that Poland’s treasury lost €7 million in 2018 due to illegal refrigerant imports valued at €55 million. Losses to the Lithuanian and Greek exchequers have been estimated at €5 million and €20 million respectively.

Recommendations

European Commission and EU member states

• Implement a fully functional per shipment HFC licensing system which allows customs officials to obtain necessary real-time information to determine if HFC imports are within the specified quota for a particular company. A first step towards this could be through a real-time quota system connecting the HFC Registry to the Single Window environment for customs and requiring the tCO2e of any bulk or equipment import to be noted on the SAD. The real-time per shipment licensing system must ensure that a company stays within its quota at all times. For example, if a company wishes to export HFCs it can only receive that credit back on its quota once the export has occurred

• Explore ways to improve reporting and monitoring of HFC trade with exporting countries, given that many of these countries are also ratifying the Kigali Amendment and will be implementing licensing systems. The iPIC system could be used to help monitor, record and collate all the data on HFC imports and exports even before controls come into force. The ICS could help provide export data to be cross-checked with import data at customs

• Make the HFC Registry more transparent in order to improve accountability. Names of new entrants and data on quotas allocated to individual companies should be publicly available

• Allocate HFC quotas at cost to reduce the pressure on customs from the rapid rise in new incumbents and to help fund the HFC licensing system

• Revise the ban on non-refillable cylinders to prohibit the use of all disposable cylinders

• Remove the exemption from the phase-down under Article 15(2) for producers or importers of less than 100 tCO2e of HFCs per year.

EU member states

• Ensure capacity-building, training and support for customs, including ensuring adequate refrigerant identifiers are available that are adaptable to test large containers

• Carry out regular risk profiling (especially of bulk imports) and customs inspections

• Set up a system to systematically compare reported data under the F-gas Regulation with customs data and investigate discrepancies

• Provide greater resources to investigate illegal HFC trade, carry out regular market surveillance and inspections including online marketplaces

• Increase penalties for Regulation infractions and ensure they are regularly applied and communicated through industry and media channels

• Carry out regular targeted awareness raising and training and ensure effective dialogue between customs and environment ministries; for example, through workshops, webinars, production of customs handbooks etc. Consider formal information sharing agreements between customs, industry and regulators

• Promote low-GWP energy efficient technologies through incentives, such as tax rebates, and additional bans on HFC-containing equipment

• Invest in the installation and servicing sector, ensuring contractors are trained and equipped to work with flammable refrigerants and to ensure the efficient recycling and reclamation of HFCs

• Reduce further demand for illegal HFCs by increasing incentives and reducing barriers to HFC reclamation.

Recommendations

European Commission and EU member states

- Implement a fully functional per shipment HFC licensing system which allows customs officials to obtain necessary real-time information to determine if HFC imports are within the specified quota for a particular company. A first step towards this could be through a real-time quota system connecting the HFC Registry to the Single Window environment for customs and requiring the tCO2e of any bulk or equipment import to be noted on the SAD. The real-time per shipment licensing system must ensure that a company stays within its quota at all times. For example, if a company wishes to export HFCs it can only receive that credit back on its quota once the export has occurred

- Explore ways to improve reporting and monitoring of HFC trade with exporting countries, given that many of these countries are also ratifying the Kigali Amendment and will be implementing licensing systems. The iPIC system could be used to help monitor, record and collate all the data on HFC imports and exports even before controls come into force. The ICS could help provide export data to be cross-checked with import data at customs

- Make the HFC Registry more transparent in order to improve accountability. Names of new entrants and data on quotas allocated to individual companies should be publicly available

- Allocate HFC quotas at cost to reduce the pressure on customs from the rapid rise in new incumbents and to help fund the HFC licensing system

- Revise the ban on non-refillable cylinders to prohibit the use of all disposable cylinders

- Remove the exemption from the phase-down under Article 15(2) for producers or importers of less than 100 tCO2e of HFCs per year.

EU member states

- Ensure capacity-building, training and support for customs, including ensuring adequate refrigerant identifiers are available that are adaptable to test large containers

- Carry out regular risk profiling (especially of bulk imports) and customs inspections

- Set up a system to systematically compare reported data under the F-gas Regulation with customs data and investigate discrepancies

- Provide greater resources to investigate illegal HFC trade, carry out regular market surveillance and inspections including online marketplaces

- Increase penalties for Regulation infractions and ensure they are regularly applied and communicated through industry and media channels

- Carry out regular targeted awareness raising and training and ensure effective dialogue between customs and environment ministries; for example, through workshops, webinars, production of customs handbooks etc. Consider formal information sharing agreements between customs, industry and regulators

- Promote low-GWP energy efficient technologies through incentives, such as tax rebates, and additional bans on HFC-containing equipment

- Invest in the installation and servicing sector, ensuring contractors are trained and equipped to work with flammable refrigerants and to ensure the efficient recycling and reclamation of HFCs

- Reduce further demand for illegal HFCs by increasing incentives and reducing barriers to HFC reclamation.

Doors wide open

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.

Doors wide open

Download the full report, detailing the results of our investigations. This includes references and picture credits.